High Road Training Partnerships Research Brief

Kait Johnson is a third-year student at UW studying Law, Societies, and Justice. They are a research assistant at the Bridges Center, where they have consulted with leaders in workforce development in Washington and beyond to understand how the state can develop more worker-centered solutions to the issues of working people.

Putting Washington on the High Road?

In this brief, we summarize select Washington workforce development programs and approaches, examine how High Road Training Partnerships (HRTPs) have operated in California, and investigate the potential opportunities for and benefits of HRTPs in Washington state. The framework for this research came from initial meetings and collaboration with Ligaya Domingo (Racial Justice and Education Director at SEIU Healthcare 1199NW and member of the Seattle-King County Workforce Development Board), Ana Luz Gonzalez-Vasquez, (Project Director for POWER in the Workforce Development at the UCLA Labor Center), and Sarah L. White (Labor Policy & Research Director, Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis). Additional framing and information was provided by Rachel McAloon (Workforce Development Director, Washington State Labor Council AFL-CIO), Casey Gallagher (California Regional Director at the Machinists Institute), Kate Dunham (Workforce and Human Services Division Director, Social Policy Research Associates), and Pamela Egan (Director of Labor-Management Partnerships at the UC Berkeley Labor Center.) We extend our gratitude to each of these individuals for their time and thoughtful input.

Introduction

In 2017, California’s Workforce Development Board (CWDB) launched a $10 million High Road Training Partnership (HRTP) initiative. Intended to promote industry collaboration across stakeholder groups, HRTP provides funding and a framework for partnerships to be undertaken by those representing the demand (employer) and supply (worker) sides of the labor market to create mutually beneficial solutions. These partnerships are incentivized to operate off of three main principles, together considered the “High Road” for employers: job quality, equity, and climate resilience.[1] The HRTP model is similar to Washington’s model of Industry Skills Panels, which started in 2000 and allowed leading regional stakeholders to convene partnerships of employers and service providers with a focus on solving workforce needs.[2]

While California’s HRTP model has continued to grow and develop, we at the Bridges Center are interested in if, and how, this model could inform local and state-wide workforce development initiatives in Washington. To further explore this, we spoke with workforce development and labor leaders in California and in Washington, and their perspectives and experiences were helpful in better understanding the complexity of the two workforce systems - as well as potential opportunities for streamlining. The following provides additional context on Washington’s workforce development system, California’s HRTP pilot and ongoing program, and ideas for moving forward.

Washington Workforce Development System Overview

Washington’s workforce development system comprises 12 Local Workforce Development Boards (LWDB), a statewide workforce board, several state agencies, and partnerships with employers, community-based organizations, and unions across the state's diverse regions. This system oversees a diverse range of industries and areas that have witnessed varying levels of success in response to the myriad challenges faced by Washington’s workforce in recent years.

Along with the rollout of the newly drafted plan and priorities, there have been and continue to be efforts to address pressing workforce issues from a worker-centered perspective that also takes into account market needs. Leading among these are numerous recognized pre-apprenticeships and registered apprenticeships throughout the state that support in providing stable employment pathways to marginalized communities.[15] And these programs are on the rise. In 2021, there were enough registered apprentices in Washington state for it to be considered the third largest “school” in the state [16], and in 2023, over $5.6 billion in federal grant money was awarded to Washington for the expansion of registered apprenticeship programs.[17]

In addition to registered apprenticeship and recognized pre-apprenticeship programs, LWDBs are also implementing practices to better center workers and their needs. In the Seattle-King County Workforce Development Council’s 2020-2024 Regional Strategic Plan, regional collaboration with stakeholders is emphasized, alongside increasing opportunity and equity for Black Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) workers. The plan goes as far as to mention how regional collaborations can promote high-road practices and ensure that new jobs fulfill workers' needs.[18] Snohomish County’s Workforce Development Council’s (called the Future Workforce Alliance) Regional Strategic Plan includes initiatives by the council and Workforce Snohomish to consult community-based organizations and form an equity and inclusion working group to assist in delivering services to underserved communities.[19] Mentioned in the 2024-2028 TAP Plan, there is also the Quality Jobs Framework, which was created by the Columbia-Willamette Workforce Collaborative and convened meetings involving labor, business, and workers to come up with a clear framework and guidance for creating high-quality jobs.[20] Cross-stakeholder collaboration is already a common practice throughout the state and is an integral part of building an equitable workforce development system.[21]

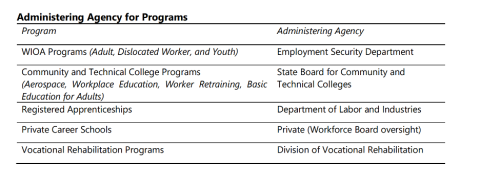

Currently, the state uses a population-based model to provide workforce development resources more than the sector-based approach observed in California’s HRTP pilot. Instead of relying directly on industry partnerships to create workforce solutions, 84% of workforce development funding in Washington runs through five state agencies. Much of that funding is then distributed to community-based organizations (CBOs) in what is called a “hub and spoke” model to provide services to whole populations at one-stop service centers. However, this method of service distribution means that people who cannot access these “one-stop locations” are underserved.[22]

California HRTP Pilot

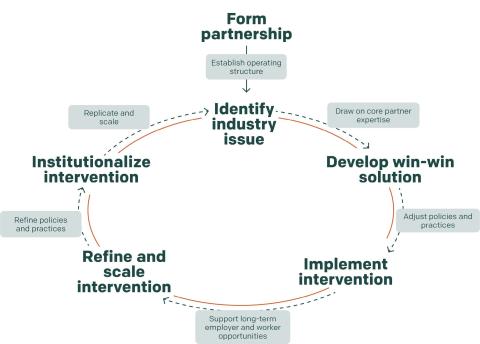

California’s pilot of the High Road Training Partnership demonstrated successful interventions in workforce development while also centering worker and employer needs for increased job quality, equity, and universal concern for climate resilience.[23] These partnerships function by placing together the demand (employers) and supply (workers) in a specific industry and considering their needs as a whole. They are often convened by a third-party organization that acts as an intermediary between employers and labor representatives (from unions or workers' organizations) in crafting mutually beneficial solutions that the convener can execute. Workforce development providers are also engaged in the execution process, alongside continued input from both parties representing workforce demand and supply. The solutions created by these partnerships help meet the needs of workers for quality, equitable jobs while providing a skilled pool of workers for employers. Partnerships may be convened to address a single issue but ideally evolve into ongoing collaborations to help address industry needs in the long term.[24] According to Casey Gallagher, a labor researcher who participated in the build-up of the pilot, the key was funding and elevating programs and partnerships that were already building solutions on the ground and putting labor organizers into the room in order to better connect with communities in need of services. At its center, the question was, “How do we get all the people who need to be in the room together for us to develop?”

The CWDB initially identified a set of HRTPs already convened over eight different sectors, including healthcare. The Shirley Ware Education Center (SWEC) convened the partnership within this sector. Established by SEIU UHW-West, SWEC brought together employers, workers, and union leaders to do a holistic assessment of needs based on worker focus groups, surveys, and interviews with collectively analyzed results. Workers were also brought on as members of a steering committee for the initiative, along with a working group that functioned as a sounding board throughout the process. Employers had identified a growing demand for allied healthcare workers, while workers in entry-level healthcare positions, such as janitorial staff and food service workers, identified time, money, and employer support as barriers to career advancement. SWEC then partnered with the local Sierra and Merritt Colleges to create a Multi-Occupation registered pre-apprenticeship program. Implementing the High Road principles of job quality, climate resilience, and equity, the program gives low-wage, traditionally marginalized workers pathways to higher-paying jobs in demand by industry employers while professionalizing skills, promoting a more environmentally friendly workplace, and creating a more sustainable environment for workers, employers, and patients alike. For example, a food service worker may get the opportunity to train in the skills necessary for a medical assistant or, eventually, a registered nurse through supportive pathways provided by SWEC’s partners.[25] The largest grant ever received by SWEC was recently awarded to expand this program, with $12 million going towards strengthening career pathway programs and support for tuition and wages for 775 participants.[26]

The partnerships sustained through the HRTP pilot continue to provide benefits for workers and, even in the face of significant state budget shortfalls, stakeholders were able to restore $25 million in funding to the program. According to the Social Policy Research Associates based out of California, the state is perhaps switching to a more population based model, similar to Washington. The pilot relied mainly on unions and their education arms to engage workers, and questions remain under investigation about how to engage workers in industries without established mechanisms for asserting worker power, such as forestry, retail, and more. In these areas, HRTPs are one potential method for building collective worker strength to push forward demands for climate resilience, job quality, and equity.

Recommendation

Although HRTPs may not be a prescriptive solution, they have proved to be a worthwhile experiment and a testament to the need for more innovative solutions that center workers and address equity, job quality, and climate. In our conversations with workforce development leaders, one critical lesson that emerged was the power of organizing. Casey Gallagher named the importance of putting organizers in the room to develop workforce solutions, and a similar sentiment was echoed by Pamela Egan at UC Berkeley’s Labor Center, who also supported the development of HRTPs in California. “The models that are able to last through the booms and busts [of funding cycles] are set up through collective bargaining,” Egan said. There is an ongoing need, in both Washington and California, to devise ways of centering worker power, rather than simply worker voice, beyond just putting people into the same room. Though this is most commonly promoted in the form of union involvement, Egan elaborated that this can also look like worker centers, worker ownership, and even jointly sponsored pre-apprenticeship like MC3 programs in the construction sector.[27]She points out that joint labor-management apprenticeship programs are the original HRTPs.

Increasing the ability of workers to “skill up” in their positions was also a major lesson taken away from HRTPs. WIOA (Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act) funding typically limits workforce development boards due to a 20% spending cap on incumbent workers,[28]. Still, California’s pilot program focused more on workers in low-wage jobs. According to Kate Dunham with Social Policy Research Associates, these workers often fly under the radar in workforce development initiatives that focus on getting people into paid positions rather than creating opportunities for mobility for those in lower-paying positions. By operating through employers and unions, HRTPs were able to invert this model and help incumbent workers “skill up” through training and certification in line with the High Road standards of equity, job quality, and climate resilience.

Washington is already laying the basis for this kind of meaningful engagement and development of worker power through training and meaningful investment in both incoming and incumbent workers. McAloon made sure to emphasize that the state has a robust program of registered apprenticeships across industries, which serves as a strong foundation upon which to innovate further and develop creative solutions for the growing challenges of ensuring high-quality and climate-resilient jobs. The 2024-2028 TAP Plan already takes many of these considerations into account with its priorities of industry (including building out the apprenticeship infrastructure) and credentialing that allow workers to advance their careers more easily. Though Washington and California’s workforce development systems operate on vastly different scales and with unique policy and regional differences, both face the difficulty of balancing the equitable distribution of workforce development resources across incredibly diverse areas with distinct industries, populations, and unionization rates. California’s pilot revealed the importance of listening to those on the ground and following worker power instead of solely worker voice, and Washington is well positioned to follow and add to these lessons.