Landscapes of Uncaring: Latina Caregivers’ Experiences in the COVID-19 Pandemic

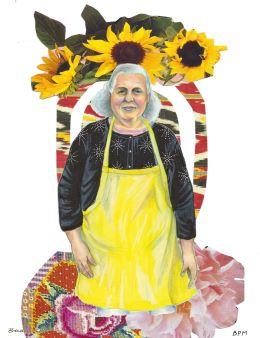

Olivia Orosco is a PhD student in the Department of Geography at UW Seattle. For this work, Orosco received funding from the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies and the Howard Martin Award from the Department of Geography. This research was the focus of Orosco’s 2022 Master’s thesis. Orosco's photo is shown at the top right of this article. Below Orosco's photo are two of the caregiver portraits done by Brianna Miller and Brando Martin.

This section pulls from the summary provided to the Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies by the researcher, Olivia Orosco.

As the ongoing pandemic restructured daily lives and led to surges in hospitalizations and deaths, the media praised the heroism of healthcare workers using the hashtag #HealthcareHeroes. However, this rhetoric of #HeroesDeLaSalud did not circulate in Spanish-language media sources – sacrifice and exploitation were already workplace expectations for Latinx immigrant workers in the United States. In many cases, the discourse of “healthcare heroes” excludes, sometimes quite viscerally, caregivers or Home Care Aides (HCAs). Orosco’s research seeks to include these vital workers by utilizing ethnographic methods, as well as collaborative portraiture with local artists to center Latina caregivers’ need for improved conditions, respect, and gratitude. The portraits were also gifts to the caregivers, some of whom requested specific artistic backgrounds, and many of whom chose to wear masks as a statement of embodied care.

Orosco conducted 15 testimonios with caregivers, who are HCAs for the elderly and persons with disabilities, from networks she established while working at a community-based resource center serving immigrants in Tacoma prior to grad school. Testimonios are a type of knowledge sharing that is based on relational storytelling and used to raise awareness and excite social change and challenge colonial academic knowledge production. This method allowed caregivers to consider how work impacts their whole selves.

Considering the racial dynamics of low-wage care work within the larger healthcare sector, this research adds the layers of the pandemic and the resulting discourse of heroism and for many workers, disposability, to investigate how caregivers understand and navigate their work.

Orosco found that caregivers or HCAs are negotiating with risk while engaging in everyday practices of embodied care. This framing of care as an embodied practice allows the process of providing care to include the feelings and actions of the caregivers. Examples of embodied care include bringing in coloring pages, dancing corridos in kitchens, and braiding others' hair. Orosco illuminates how Latina HCAs see themselves as expressing agency through the ways they do this work, though they know that clients do not always disclose all their information, they know that employers lie to them, and they know that the public does not value their work.

Orosco’s testimonios go beyond “healthcare heroes” - to the daily realities. What about the workers who must work to live? What about those who have no interest in being heroes, but show up to work because that is what they did every other day? How do they understand and navigate COVID-19 precarity and their labor? These questions are particularly crucial for Latino workers, as the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) found, most recently accessed in February 2022, that “Hispanic or Latino persons” have some of the highest rates of cases and deaths of any ethnic group. Many caregivers participating in this research contracted COVID-19 through dangerous work environments, which affected their health, the health of their family, and their financial stability.

Findings from the testimonios include:

- HCAs or caregivers know that their work is essential because of the ways in which their care makes others’ lives possible.

- HCAs are entangled between the dynamics of the cared for, the cared for’s family, the state of Washington, and the private and non-profit agencies contracting them. The tension of the personal and the structural affects all aspects of their work.

- As with most social reproduction, this work is feminized and when outsourced, as it is often, carried out by low-paid women of color and immigrants. Grace Chang’s 2016 work, Disposable Domestics: Immigrant women workers in the global economy, provides further insight into social reproduction and identity trends associated with it.

- Though the context in which caregivers work is specific to their clients, agency, and personal experience, they work and exist within a politicized space shaped by structures of power.

Findings from the testimonios emphasized that regardless of whether they are seen as “healthcare heroes”, caregivers know their practices of care are and continue to be essential to the community. Providing care is multifaceted. Care is uneven. HCAs have their care for clients unreciprocated and exploited in the uncaring landscape of their workplaces, of the neoliberal state, and beyond. However, care is also expansive, creative, and facilitates a diverse web of support that allows caregivers to survive and find deep meaning in their work. Through their work providing care in the homes of the elderly and people with disabilities, caregivers are made aware of the interdependence of community, and the true value of the work they do.